Steve Izenour: Aesthetically Incorrect

Hot Air Gallery, New York November 30 2018.

Content curation by Daniel Horowitz and Matt Shaw. Text by Matt Shaw.

Gallery concept and design by Matt Shaw and Bika Rebek

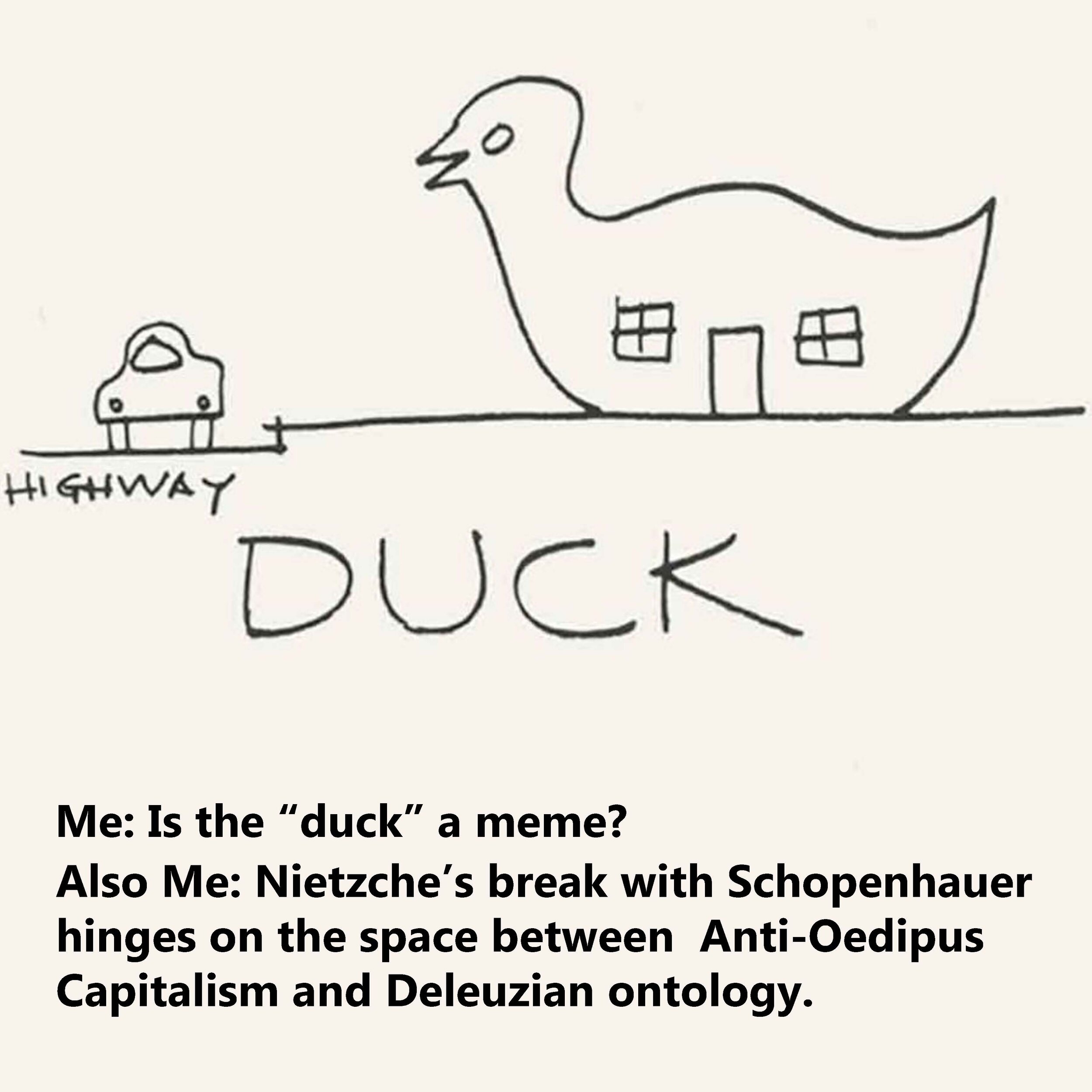

Steven Izenour (Ize) was an influential protagonist of pop architecture in the 20th century. He ran the infamous Las Vegas studio with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown at Yale and was the third author of the subsequent book Learning from Las Vegas. As a principal at the firm VSBA, he continued this tradition in a series of “Learning from” studios at various schools, most notable “Learning from Wildwood, NJ”, a look at the boardwalks, motels, and attractions of the seaside town on the southern tip of the Jersey Shore and the home of doo-wop, and thus doo-wop architecture, a mid-century commercial vernacular and variant of Googie.

HOT AIR’s exhibition Steven Izenour: Aesthetically Incorrect takes its name from correspondence in which Ize laments AC, or “aesthetic correctness”, a pun on the very 90s term PC, or political correctness. We will be showing never-before-seen archival material and imagery alongside other artifacts and will have free burgers for the first 100 people and a special playlist dedicated to the Ize and Wildwood.

HOT AIR is a DIY architecture space in downtown Manhattan that provides a platform outside of the traditional institutions of New York City. Operated out of abandoned and vacant storefronts, the initial iteration will be in the former home of Haute Air, “a boutique blow dry bar in the heart of Soho." Located in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the world, HOT AIR paradoxically benefits from the extreme gentrification that has made Manhattan less hospitable to artists. By reclaiming space left behind by this perverse logic of capital, HOT AIR is part of another stage of gentrification. In this post-commercial context, next to brand flagships and private clubs, HOT AIR itself is purposefully casual and Lo-fi, providing a place for fast, loose, and unpolished ideas—a counterpoint to the corporate aesthetics that now dominate the city.

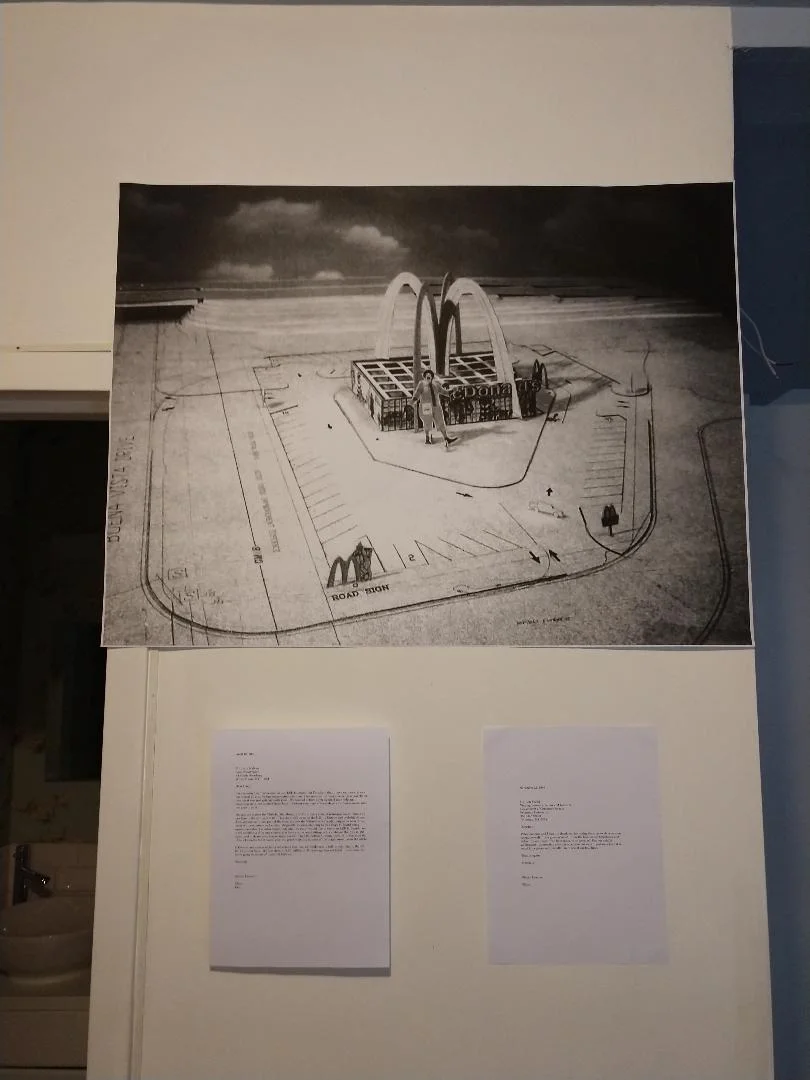

Ize was deeply invested in pop architecture and the outlandish signage of roadside America. He wrote about the messy vitality and importance of inclusivity in the built environment, often in a loose, manifesto-like prose. It could be said that he was even more deeply invested in pop culture than other architects of his time. His design projects included work for Disney— a welcome center and a McDonald’s which was unfortunately never built. Izenour also was a great appreciator of the American commercial landscape, and wrote a book about White Tower restaurants, entitled White Towers, which was a serious look at the hamburger chain’s distinctive branding, which centered around the image of the white tower.

Ize had a distinctive interest in emerging technologies and was consistently searching for ways to continue the VSBA project into the 21st century. He was infatuated with “Jumbotrons” in the 1990s and was always looking for a way to get one into a project. He was invested in the car as a technology, but also in new internet and illumination methods that might make architecture communicate and come alive in new ways. In a 1999 panel titled “Social Context of the Internet and the Family,” he pondered Palm Pilots and cited Wired magazine. Unfortunately, due to his untimely death in 2001, he never got to see the consequences of these technologies.

The son of George Izenour, an influential theater architect, Ize was always know to have a big heart and a rebellious personality. Beloved by his staff, and often took interns on McDonalds runs. He was also known to be good with clients and friendly to other architects, who considered him an important part of the conversation. In 1982 he designed a house on Long Island Sound for his parents, considered to be one of the most cartoonish VSBA projects.

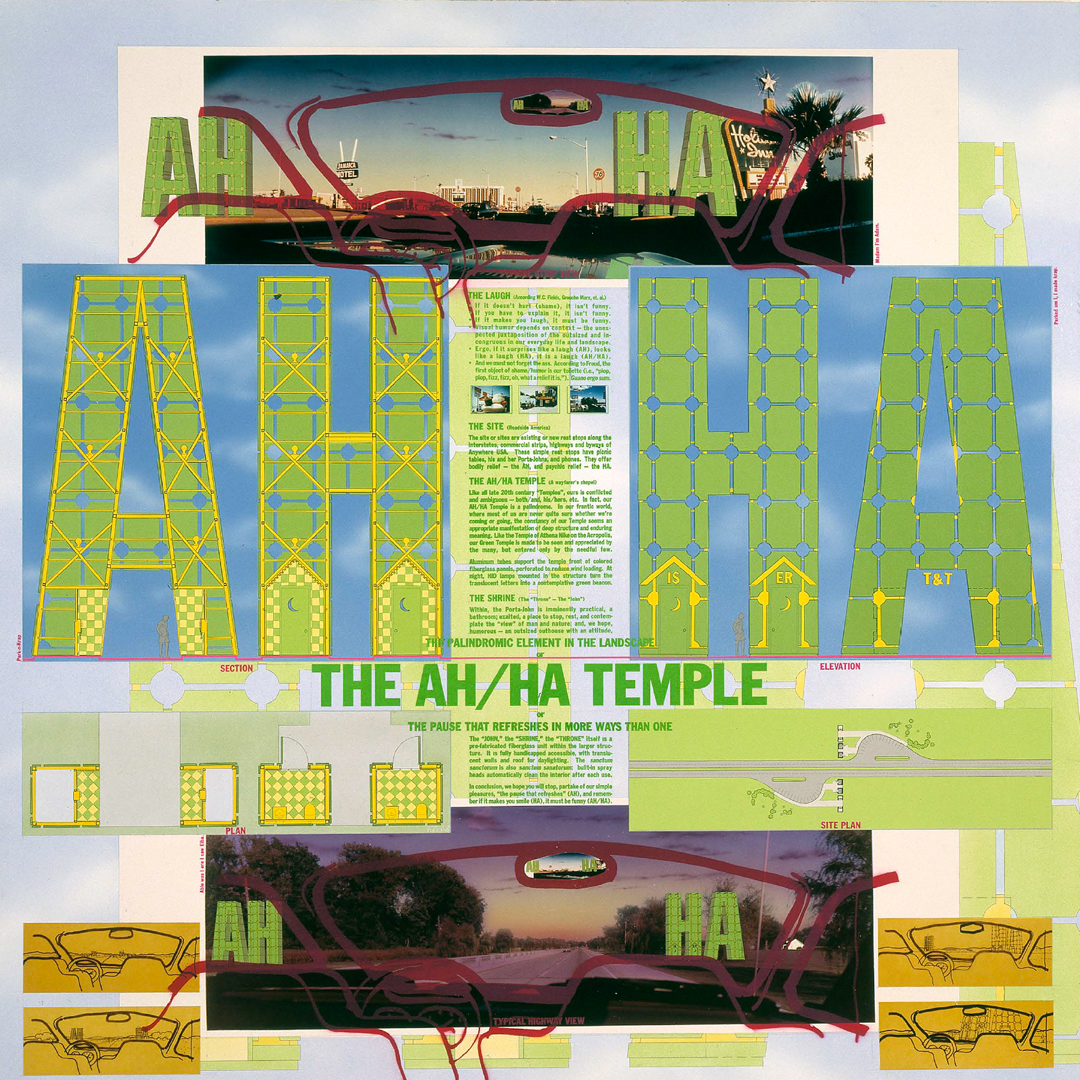

The AH/HA Temple

This outlandish roadside attraction was a competition entry that Ize worked on outside of his role at VSBA. The giant letters, meant to be read the same form the front or rear window of a car, were a monument to laughter, as well as a brief rest (stop) from the road. The AH’s and HA’s contained his and hers restrooms, and a pair of phone booths. While the entry was wildly unsuccessful in what Ize thought was a rigged, unfunny jury, he still used the project to pitch to people he thought might be sympathetic to the humor and utility of the idea.

Daniel Horowitz worked in the office of VSBA in the 1990’s and worked with Steven Izenour on the AHHA competition entry.